My family moved from Germany to the United States when I was five, and we eventually ended up in Asheville, NC. Surrounded by the Appalachian mountains, I spent most of my youth exploring their diverse forests. My sophomore year in high school, I spent a summer taking a course in Field Wildlife Biology through Summer Ventures in Science and Math at UNC-Charlotte; we spent most of our time in Chimney Rock Park, NC. In the last few summers of high school, I worked for David Danley of the USDA Forest Service. I spent many summer days on the Blue Ridge Parkway collecting seeds of native grasses and flowers. With David as a mentor, I began to become more intimately acquainted with the diverse flora of the Appalachian forests.

I first became interested in ecological research my sophomore year at Washington & Lee University (2000). Under the direction and support of Dr. Hurd, I initiated my first research project testing whether praying mantids ate pollen, and if so, what benefits mantids obtained in survival, weight gain, and fecundity. This work led to my Honors Thesis entitled, "Pollen feeding and its effect on a generalist predator, the Chinese praying manitd Tenodera sinensis" and a publication in Environmental Entomology. In the midst of my praying mantid madness, I also began to work on various projects led by Dr. Marsh investigating the effects of roads and streams on the behavior and movement of red-backed salamanders (see Publications ).

My junior year (2001) of college I took Ornithology with Dr. Cabe. I gave bird walks at Boxerwood Gardens during college and taught Ornithology at Nature Camp the summer following graduation. Following Nature Camp, I hopped on a plane to Australia to work on Dr. Borgia’s project on sexual selection in Bowerbirds. I spent many hours observing bowerbirds as well as any wildlife that walked, hopped, flew or slithered by. I continued working with salamanders the following summer, but would sneak away several early mornings to accompany the Junco Lab at Mountain Lake.

In between studying salamanders, I was also a lab manager at the University of Washington in Dr. Tewksbury’s lab, which was testing several hypotheses determining the function of secondary metabolites in fruits and their importance in mediating interactions between plants and seed dispersers, seed predators and fruit pathogens.

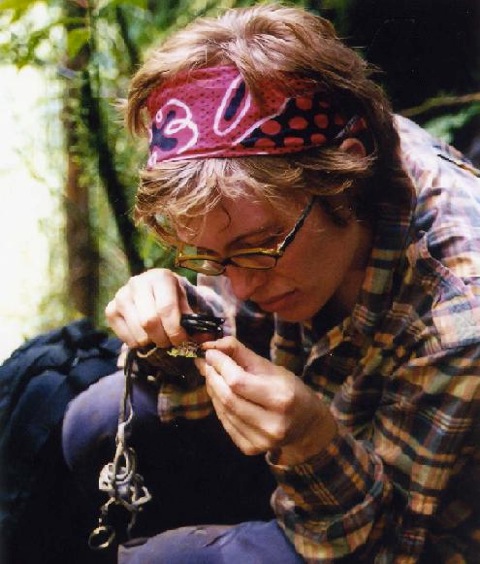

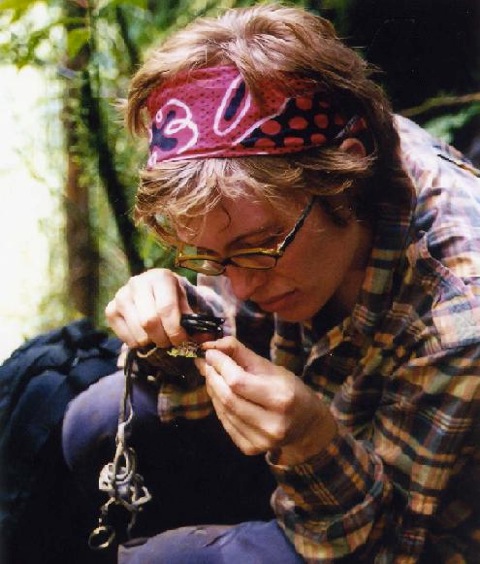

In between these intellectual ventures in ornithology, sexual selection, evolutionary and community ecology, I also was becoming passionate about tropical landscapes. My introduction to the tropics was a six-week Botany course: four weeks in Lexington, VA and two weeks in La Selva, Costa Rica (2000). I met Lou Jost in Ecuador two years later, when I returned to the Neotropics as a student of biodiversity. With Lou as my mentor, I backpacked through the Llagnates in Ecuador, becoming acquainted with the flora while collecting Teagueia orchids.

These early experiences in the temperate zone and in the tropics aroused my fascination in biodiversity and my interest in the following questions: What are the mechanisms that maintain species coexistence? How do these mechanisms vary along latitudinal, elevational, and precipitation gradients? What role do animals and pathogens play in a plant’s lifetime and how do these interactions affect coexistence? This led me to pursue a doctorate at the University of Minnesota with Drs. Helene Muller-Landau and Claudia Neuhauser as my co-advisors. My dissertation investigated the effects of vertebrates, insects, and pathogens on patterns of early plant recruitment in tropical forests.

Drawing by Natalie Beckman

Drawing by Natalie Beckman